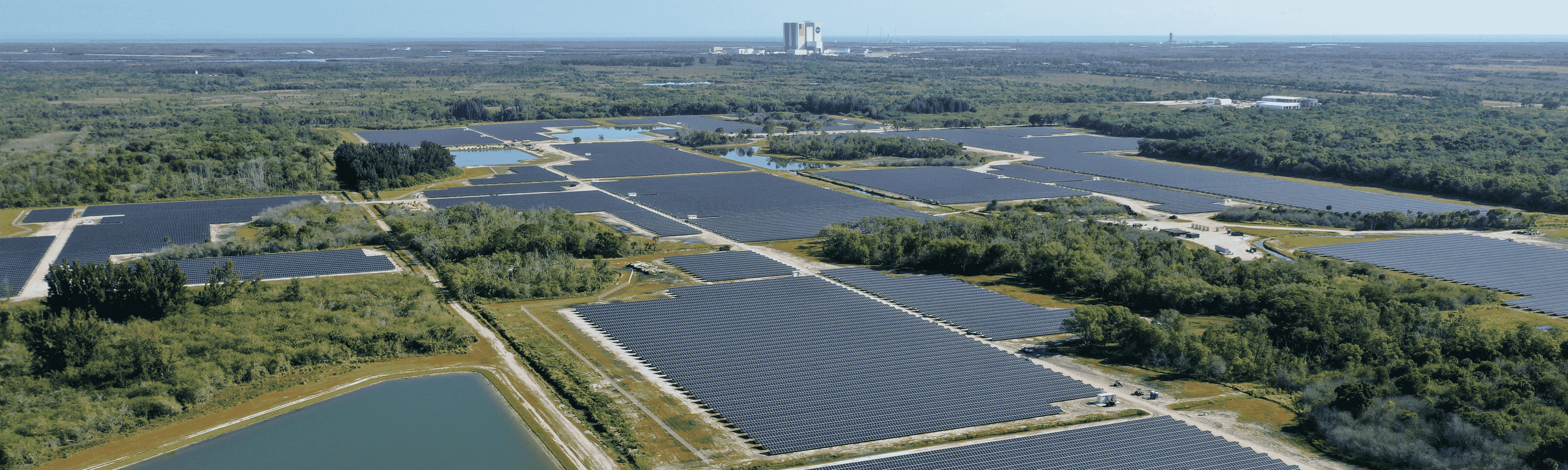

- Solar panels need a lot of elbow room. Five to ten acres of space are required to generate about one megawatt of solar electricity, which can power about 110 homes in Maryland.

- Maryland’s solar energy growth is on a deadline. Recent legislation requires that Maryland produce 14.5% of its energy from solar by 2030.

- Size matters. Community-scale and utility-scale solar often differ in terms of ownership, customers, cost, size, and location. Community-scale solar projects usually generate power for local homes and businesses. Utility-scale solar developments are often owned by remote private companies providing electricity to businesses and industrial operations that are farther away.

- Utility-scale solar projects require utility-scale transmission lines. The grid has three main components: generation (where energy is produced, like a group of solar panels), transmission (meaning the large, high voltage transmission corridors that move energy away from the site of generation), and distribution (this refers to smaller lines, like those running above a town’s sidewalk that distribute lower voltage power to homes and businesses). Community-scale solar can skip directly from generation to distribution. But most utility-scale solar must be located close to large, high voltage infrastructure for transmission.

- Most community solar stays local. Community-scale solar projects in Maryland provide power locally through the electric distribution grid. 40% of a community scale solar project’s output is required to serve low-to-moderate income customers, providing them electricity at a lower cost.

- Solar energy is inefficient compared to other renewables. The average solar panel currently in use has an efficiency rating of between 15-20%, this means that the average panel can turn about 20% of sunlight into usable energy. On a cloudy day they might only capture 6% or less of available sunlight. Wind turbines are roughly 50% efficient at converting wind into usable energy. And today’s hydroelectric plants operate close to 90% efficiency.

- Solar panels do not last forever. The average lifespan of a solar panel is about 25-30 years. Currently, about 90% of solar panels aren’t recycled, instead winding up in landfills after their useful life.

- Utility-scale solar projects in Maryland receive special treatment. In Maryland, utility-scale solar projects can qualify for something called “preemption” from nearly all local land use regulations, which means that the same process that applies for building houses, stores, warehouses, or nearly every other type of development, doesn’t apply to solar development.

- Solar knows no state boundaries. Maryland is part of the PJM Interconnection, a regional transmission organization (RTO) that includes 13 states and the District of Columbia. This means that there is no guarantee utility-scale solar power generated in Maryland stays in Maryland. Instead, it could be headed for Illinois or Indiana.

- Solar for on-farm use is A-OK. Modest solar development is permitted on ESLC conservation easements, but the power generated from those panels is strictly for on-farm use. Several farms protected by ESLC utilize solar in this way.

Solar Farm Photo c/o Nasa