What is a Mosaic?

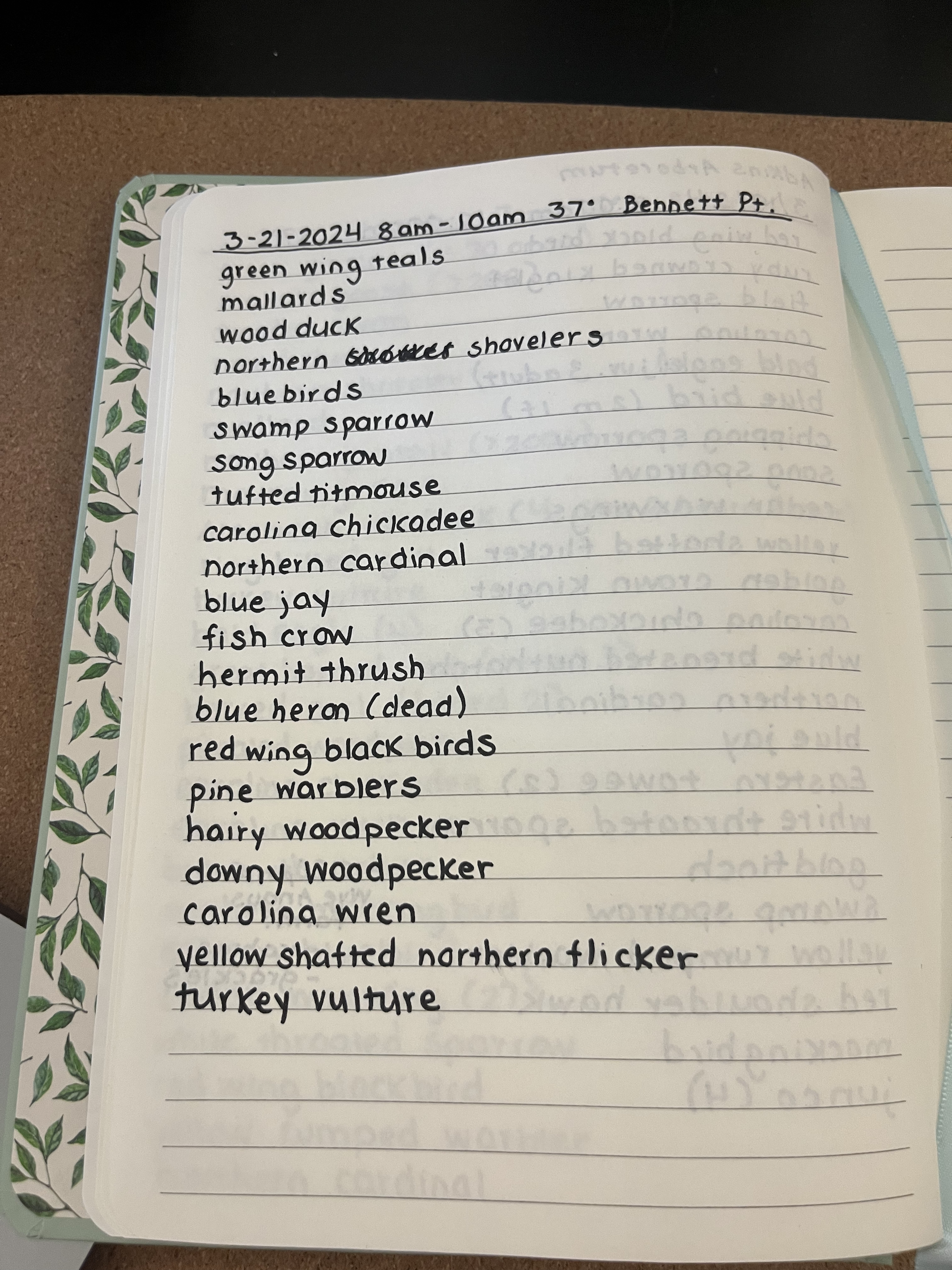

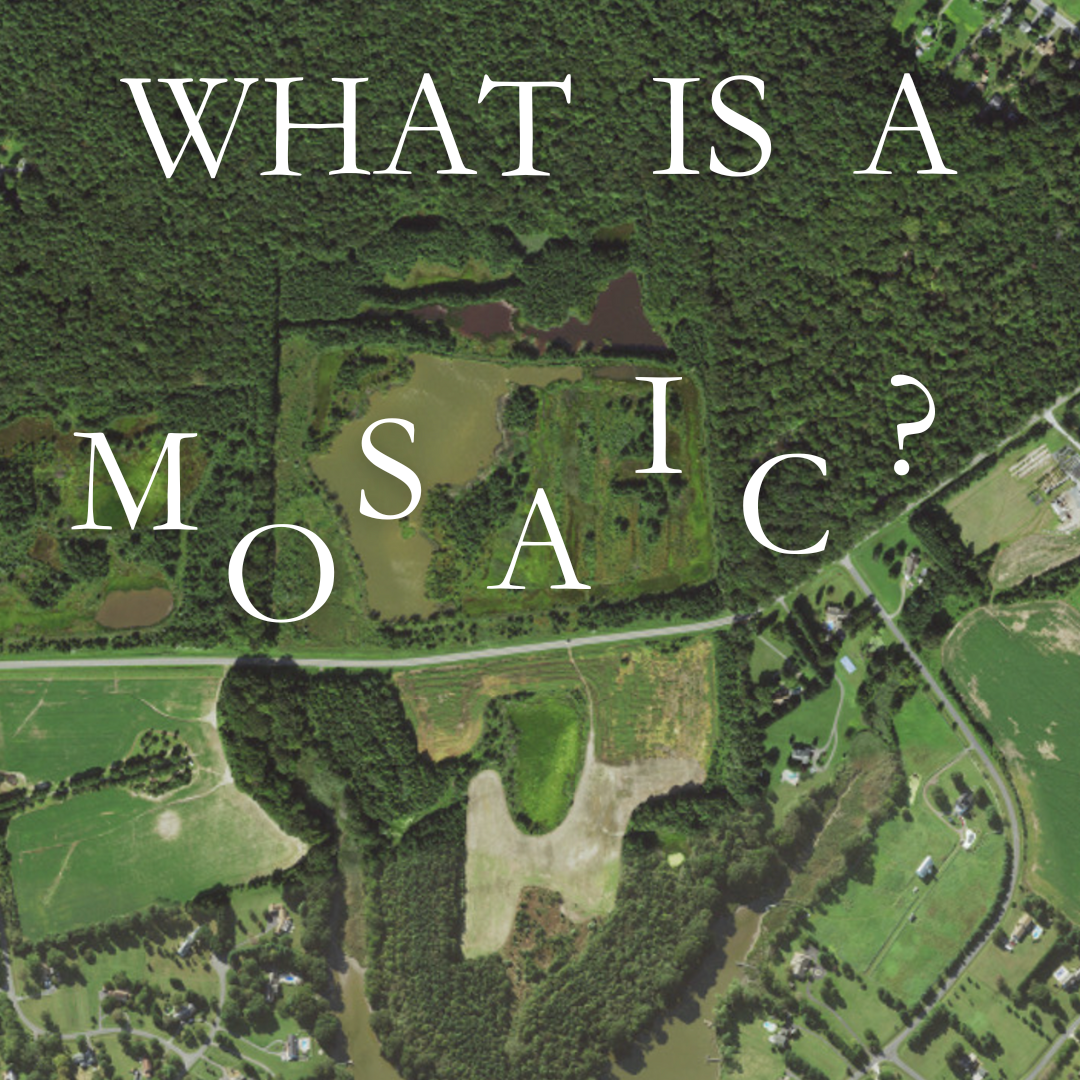

For the second gathering of the 2024 Bird Conservation Series, Eastern Shore Land Conservancy and a group of community members enjoyed an exclusive birding walk at Bennett Point Preserve, a 284-acre conservation easement in Queenstown that is usually closed to the public. Jointly owned by ESLC and Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage (CWH) since 1998, this special property has been managed by CWH to benefit wildlife.

Migrating waterfowl are known to find peace from disturbance here during both spring and fall migrations. The restored wetlands have provided sanctuary for mallards, American black ducks, northern pintails, gadwalls, American widgeons, northern shovelers, blue-winged and green-winged teals, Canada geese, young tundra swans, pied-billed grebes and countless other waterfowl. Dragonflies and bats, raptors and salamanders, snakes and beavers all call Bennett Point home. Why is the preserve so abundant with thriving wildlife? One big reason: there are no people at Bennett Point to startle these visitors away. The second? Bennett Point Preserve is a mosaic.

Not unlike the ceramic-and-grout tile mosaics of Portugal or artist Jen Wagner’s glassy blue mosaic that wraps around the outside of Easton’s Eastern Shore Conservation Center, an ecological mosaic is a also a colorful clustered patchwork but instead of tiles, the pieces are diverse ecosystems and communities. Bennett Point Preserve is quite the mosaic. Just as Maryland is “America in miniature,” Bennett Point is “Maryland in miniature,” containing a diverse labyrinth of habitats that are increasingly uncommon to find clustered so close together. Emergent wetlands, grassland, vernal pools, and maturing forest all intertwine here in a lively sanctuary harboring an ark’s worth of wildlife. Here species who depend on other species can actually find one another. The salamander can find its algae. The beetle can find its niche in the dam thanks to the beaver. Bennett Point Preserve’s multiple habitat types also provide refuge for species that can survive in multiple types of habitats should major disturbance occur – deer, for example, survive just as well in forests as grasslands, so if a grassland is burned, deer can find refuge in the un-impacted forest. And while we appreciate each of the preserve’s special habitats for their many unique identities—the canopied forest at Bennett Point is tall, shady, and loud with songbirds, the wetlands are large, spacious, and rich with invertebrates—the thing that stands out most of all are the fringes in between. In other words, if Bennett Point were a ceramic mosaic, the tiles would be lovely, but we’d all be taken aback by the grout.

In ecology-speak, the ”grout” of a mosaic of habitats is an “ecotone,” or an area of land that connects or transitions one habitat type to another. Ecotones can be large or small. At Bennett Point an ecotone might be a strip of shrub and scrub between a forest and a wetland. In your backyard it might be the unmown thicket between the shed and the fence or woods beyond. These margins between adjacent habitat types have enormous benefits for a huge diversity of wildlife. Sparrows constantly bridge these grout-y gaps as they forage in grasslands for berries and seeds then return to the forest for cover. Box turtles need forest for burrowing and shelter but tiptoe through the ecotone to cool off in water on hot summer days or burrow into the mud of a saturated bank. And the wood duck inhabits the ecotone between forest and wetland so that it can access a breakfast of pondweeds, a lunch of snails on the fringe of the pond, and a final rest-and-nest in the trees just past the snail-y grass.

ESLC’s recent birding walk at the preserve provided ample evidence of this mosaic and ecotone success. Most of the species diversity was found on the edges of each habitat. To the left, a dabbling teal in the middle of the wetlands, to the right, a downy woodpecker pecking away at a pine tree visible through the trees inside the forest. In the in-between edges of forest, field, and wetland was a bustle of a little bit of everything: sparrows, blackbirds, hawks, warblers.

Of course, creating these “edge” habitats is a matter of nuance. More edge is not necessarily better. Large, intact wildlife “cores” that contain ample space to promote genetic diversity and provide resource needs are crucial to supporting specific species of wildlife that don’t utilize ecotones or edge habitats as much, such as forest birds or salamanders. But edges in particular are under threat. Ecotones between habitats are becoming increasingly uncommon with development patterns. Rather than edges between grasses and forests, it is more common to see edges between forests and residential developments. ESLC is at work protecting these vital wildlife cores through land protection across the Eastern Shore (not just as Bennett Point) and we work to support restoration that uplifts the ecological needs of sensitive core species while providing the benefits of mosaics and ecotones. We appreciate those glossy tiles. But we also appreciate the grout.